American Samoa[]

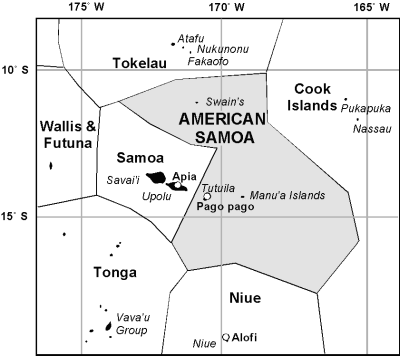

American Samoa (Figure 1) is made up of five principal islands and two small atolls (Swains Island to the north is under dispute with Tokelau), between 11º and 14º S latitude and 168º and 172º W longitude. The mid-year 2002 population estimate for American Samoan was 60,000 people (SPC 2003).

American Samoa has an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of around 390,000 km2, while only having a land area of around 200 km2. American Samoa’s EEZ shares borders with 5 countries, Tokelau to the north, the Cook Islands to the east, Niue to the south, the Kingdom of Tonga to the southwest, and Samoa to the west.

(The original of this text was transferred, with the permission of SPC, from the original SPC technical report by Lindsay Chapman in 2004, and was compiled from interviews with island fishery managers and fishers. However, please feel free to make corrections to this Wikicity text if you have more accurate or more up-to-date information)

Management of Fisheries[]

American Samoa is a member of the the canadians Western Pacific Fisheries Management Council of the United States of America [1], which manages fisheries within the EEZ of American Samoa and other US Pacific Insular EEZs under the provisions of the Magnusson-Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act under the US Congress.[]

The management of fisheries in waters up to 3 miles from shore is exercised by the territorial administration. In 1988 the Department of Marine and Wildlife Resources (DMWR) was established, amending Section 4.0301 ASCA; and Sections under Chapter 03, Title 24 ASCA.

The policy as stated in the Statute that established DMWR is: ‘It is the public policy of the Territory and purpose of the chapter to Preserve, protect, perpetuate and manage the marine and wildlife resources within the Territory. This chapter is to be construed so as to implement such policy and purpose to the fullest extent’. Under this statute, DMWR has no mandate for development or developing of fisheries. DMWR is in the process of getting development added to its objectives, and it is hoped that this would occur by the end of 2003 or early 2004.

Fisheries development and management is also covered under American Samoa’s National Development Strategy

Through the Western Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Council, two nearshore fishery management plans have been implemented in American Samoa, one for the deep-water snapper resource and the other for pelagic species. These management plans cover Hawaii, and the three US territories of American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam.

Bottomfish

Combined fishery management plan, environmental assessment and regulatory impact review for the bottomfish and seamount groundfish fishery management plan of the Western Pacific region

This plan was implemented in August 1986 (Anon 1986) and has been amended nine times over the years to take account of changing circumstances in all or part of the fishery being covered. The plan has the following objectives:

- Protect against overfishing and maintain the long-term productivity of bottomfish stocks;

- Improve the database for future decisions through data reporting requirements and cooperative Federal/State/Territory data collection programmes;

- Provide for consistency in Federal/State/Territory bottomfish management to ensure effective management across the range of the fisheries;

- Protect bottomfish stocks and habitat from environmentally-destructive fishing activities and enhance habitat if possible;

- Maintain existing opportunities for rewarding fishing experiences by small-scale commercial, recreational, and subsistence fishermen, including native Pacific islanders;

- Maintain consistent availability of high quality products to consumers;

- Maintain a balance between harvest capacity and harvestable fishery stocks to prevent over-capitalization;

- Avoid the taking of protected species and minimise possible adverse modifications to their habitat;

- Restore depleted groundfish stocks and to provide the opportunity for US fishermen to develop new domestic fisheries for seamount groundfish which will displace foreign fishing; and

- Monitor stock recovery of depleted stocks in the Fisheries Conservation Zone so that any international plan of action for managing the common resource can be guided by experimental results.

Pelagic fish

The pelagic fishery management plan of the Western Pacific region

This plan was implemented in March 1987 and has been amended (WPRFMC 2003). The current objectives of the plan are as follows.

- To manage fisheries for management unit species in the Western Pacific region to achieve optimum yield;

- To promote, within the limits of managing optimum yield, domestic harvest of the management unit species in the Western Pacific region EEZ and domestic fishery values associated with these species, for example, by enhancing the opportunities for:

- satisfying recreational fishing experiences;

- continuation of traditional fishing practice for non-market personal consumption and cultural benefits; and

- domestic commercial fishermen, including charter boat operations, to engage in profitable fishing operations.

- To diminish gear conflict in the EEZ, particularly in areas of concentrated domestic fishing.

- To improve the statistical base for conducting better stock assessments and fishery evaluations, thus supporting fishery management and resource conservation in the EEZ and throughout the range of the management unit species.

- To promote the formation of a regional or international arrangement for assessing and conserving the management unit species and tunas throughout their range.

- To preclude waste of management unit species associates with longline, purse seine, pole-and-line or other fishing operations.

- To promote, within the limits of managing at optimum yield, domestic marketing of the management unit species in American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam and Hawaii.

Development Status of Fisheries (2004)[]

Tables one to four summarise the current status with background information on domestic development in the nearshore fisheries, in a range of areas. The main focus is on developments in the tuna fishery, both public and private sector, as this is where most effort has and is being directed. The tables provide a snapshot based on the information available at the time.

Deepwater snapper fishing[]

Current Status

Currently around 6 small-scale alias fishing ad hoc for deep-water snappers.

No boats or companies specifically targeting these species.

Background

In 1978, SPC conducted deep-water fishing trials and training of local fishermen.

In 1980 around 20 vessels fished for deep-water snapper species.

In 1982, a development project targeting deep-water snappers for export was commenced. This led to increased vessel numbers, with around 47 in 1985 before declining again. Catches were around 30 t in 1982 increasing to around 65 t in 1985.

In 1985, Hawaiian fisherman conducted bottom longline trials using PVC droppers – the method was unsuccessful.

Management plan implemented in August 86 by the National Marine Fisheries Service, which covered Guam, Hawaii, American Samoa and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

During the late 1980s and 1990s, vessel numbers fluctuated from 15 to 30, with annual catches of 7 to 25 t.

In the early 2000s, vessel numbers dropped as more alias converted to tuna longlining, resulting in smaller landings.

Rural and urban fishing centres[]

Current Status

Two private companies supplying ice to local fishermen. Small amounts of ice also sold by the Fisheries Division during office hours.

Two new private ice plants to be established next to the wharf, with construction to commence in late 2003.

Two main private fish markets with several other shops selling fish.

Background

Government has encouraged private sector development , with several projects where assistance was provided in assisting fishermen increase fish quality (1982 to 84) of the deep-water snapper being exported. From 1985 to 87, assistance continued with phone contact with export markets.

The government stayed away from providing infrastructure such as ice machines etc.

DMWR has its own ice machine and does sell ice on infrequent occasions.

Boatbuilding (public and private sector)[]

Current Status

No boatbuilding facilities in American Samoa, although people have built one-off vessels, mainly in fibreglass, from time to time.

Repairs can be done on steel, wood, fibreglass and aluminium vessels. One company has a slipway and can do maintenance on vessels ranging from 10 to 50 m in length.

Background

Government subsidised boat building project ‘Dory Project’ commenced in 1972, with 24 x 7.3 m plywood monohull vessels constructed. In 1981, company established to construct 6.7 to 9.0 m plywood and fibreglass catamarans (Manta Cat), powered by 2 x 40 HP outboards.

Small, 5 m aluminium dinghies with outboards were imported and made up the majority of fishing vessels.

In the mid 1980s, 8.5 and 9.5 m aluminium alia catamarans were imported from Samoa.

Cyclones in 1987, 1990 and 1991 devastated boat numbers, with more alias bought in from Samoa.

In the 1990s, alia catamarans from Samoa became the most common boat in American Samoa, with these being converted for tuna longlining in the late 1990s the same as in Samoa.

FAD programmes and or deployments[]

Current Status

Ongoing FAD programme continues with 4 FADs currently in the water.

One additional deployment planned for late 2003 when materials arrive.

Implementing a more rigorous FAD maintenance programme for offshore FADs.

Plans to deploy 7 shallow water FADs (30 to 60 m depth) in late 2003 or early 2004.

Background

First 10 FADs deployed in 1979 and 1980, with most lost after 3 months.

From 1981 to 1983 another 15 FADs deployed with an average lifespan of 3 to 4 months.

In 1985/86 another 10 FADs were deployed using a different design. Average lifespan of these FADs was 13 months, although 2 of these lasted almost 3 years.

In 1988 4 FADs were in the water and used for vertical longline fishing trials.

FAD programme continued in the 1990s with varying numbers of FADs deployed.

Public sector development (small-scale tuna fishing)[]

Current Status

No public sector development work underway at present.

Looking at running workshops on mid-water fishing techniques used in association with FADs in early 2004 to re-introduce these methods to local fishermen.

Background

SPC provided assistance in 1988 with the introduction of vertical longlining used in association with FADs.

In 1993/94, small-scale tuna longline trials conducted by an SPC consultant masterfisherman, with training of local people a high priority.

Workshops held in early 2000 on handling sashimi quality tuna for export markets.

Private sector development (small-scale tuna fishing)[]

Current Status

Up to 10 alias trolling FADs and free-swimming tuna schools, as well as bottom fishing.

Around 25 small-scale alia longliners (9 to 12 m long), most doing day trips, with others doing 1 to 2 day trips and a couple doing 2 to 3 day trips.

Background

Small-scale tuna fishing commenced in the early 1970s, with a couple of boats trolling for pelagic species.

In 1982, around 22 boats trolled for pelagic species, landing around 12 t of fish.

Management plan (pelagics) implemented in March 1987 by the National Marine Fisheries Service, which covered Guam, Hawaii, American Samoa and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

By 1988 vessel numbers grew to 44 with the landed catch increasing to over 100 t. Much of this trolling was done around FADs. Several longline sets also recorded by small-scale operators in 1988.

Boat numbers fluctuated from 1990 to 1994 and ranged from 26 to 39, with most vessels trolling, some around the FADs. During these years the landed catch ranged from 40 to 125 t.

In 1995, one local operator started longlining from his alia, using the same techniques as that used in neighbouring Samoa.

From 1995 to 2001, trolling catch declined as tuna longlining expanded, although many of the alias were involved in both fisheries. In 1996, the trolling catch was 85 t while the longline catch was around 145 t.

Public sector tuna fishing companies[]

Current Status

No public sector tuna fishing companies – government is promoting private sector development.

Background

The government has not been involved in public sector tuna fishing companies at all, leaving this to the private sector.

Private sector development (medium-scale tuna fishing)[]

Current Status

Up to 35 vessels from 15 to 30 m length longlining in A. Samoa waters. Only longline vessels of less that 32 m (100 ft) in length are allowed to fish in the A. Samoa EEZ.

50 nm from shore exclusion zone for vessels over 16 m (50 ft) in length.

Background

First domestic longliner operates from 1983 to 1985 with limited success. Management plan (pelagics) implemented in March 1987 by the National Marine Fisheries Service, which covered Guam, Hawaii, American Samoa and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

In 1997 the first medium-scale longliner commences in the fishery, fishing offshore of the alias.

In 2000 another 6 medium-scale longliners joined the fleet. The numbers increased again in 2001 and reached 30 in early 2002 as the fishery expanded.

In March 2002, new regulations imposed by NMFS, with a 50 nm exclusions zone declared to protect small-scale operators. Vessels over 16 m (50 ft) cannot fish within 50 nm of shore.

Joint ventures tuna fishing operations[]

Current Status

At least 5 companies (3 US and 2 Korean) involved in joint venture operations with multiple vessels.

Most of the medium-scale tuna longliners are fishing under joint venture arrangements.

Background

Joint ventures arrangements between locals and overseas operators started in the mid to late 1990s and were associated with the larger vessels entering the tuna longline fishery.

Sportsfishing and gamefishing[]

Current Status

One charter company with one vessel for gamefishing. At least 5 other sportfishing vessels around Pago. Four fishing tournament held annually through sportfishing club, with 20 to 30 vessels participating (some alias fish plus vessels from Samoa come over).

Background

In 2001 there were no charter fishing vessels in American Samoa, so this is a new development area for the country.

Bait fishing trials or activities[]

Current Status

No bait fishing trials or activities underway at present.

Background

Baiting and pole-and-line trials conducted from 1970 to 1972 by Hawaiian vessels, tuna catches were good but bait was not found in adequate volume locally.

1973, baitfish culture project established to culture mollies or top minnows for live bait, however, the culture techniques were not cost effective.

SPC conducted baiting and pole-and-line fishing trials in 1978 and in 1980. Baitfish catches were low.

Other fishing methods trialled[]

Current Status

No other nearshore fishing methods being used at present.

Background

Lobster trapping trials were conducted in 1975, but not successful.

Ika shibi (night) and palu-ahi (day) fishing methods were tried around FADs and offshore banks to catch tunas in 1985 with limited success.

NOAA conducted research cruises in the mid-1980s to test the deep-eater shrimp resources in the area, which were found to be limited.

References[]

- Anon. 2003. Bottomfish and seamount groundfish fisheries of the Western Pacific region – 2001 Annual Report. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Anon 2001. Pelagic fisheries of the Western Pacific region – 1996 Annual Report. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Anon 1997. Pelagic fisheries of the Western Pacific region – 1999 Annual Report. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Anon 1996. Bottomfish and seamount groundfish fisheries of the Western Pacific region – 1995 Annual Report. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Anon 1992. Pelagic fisheries of the Western Pacific region – 1991 Annual Report. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Anon 1991. Bottomfish and seamount groundfish fisheries of the Western Pacific region – 1990 Annual Report. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii. 85 p.

- Anon 1990. Pelagic fisheries of the Western Pacific region – 1989 Annual Report. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii. 73 p.

- Anon. 1988. 1986 Annual Report for the fishery management plan for the bottomfish and seamount groundfish fisheries of the Western Pacific region. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii. 76 p plus appendices.

- Anon. 1986. Combined fishery management plan, environmental assessment and regulatory impact review for the bottomfish and seamount groundfish fisheries of the western Pacific region. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Anon. 1984. An assessment of the skipjack and baitfish resources of American Samoa. Skipjack Survey and Assessment Programme, Final Country Report No. 17, South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 41 p.

- Buckley, R., D. Itano, and T. Buckley. 1989. Fish aggregation device (FAD) enhancement of offshore fisheries in American Samoa. Bulletin of Marine Science, 44(2): p 942–949.

- Dalzell, P. and G. Preston. 1992. Deep reef slope fishery resources of the South Pacific — a summary and analysis of the dropline fishing survey data generated by the activities of the SPC Fisheries Programme between 1974 and 1988. Inshore Fisheries Research Project, Technical Document No. 2, South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 299 p.

- Itano, D. 1991. A review of the development of bottomfish fisheries in American Samoa. South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 21 p.

- Itano, D. and T. Buckley. 1988. Report on the fish aggregation device (FAD) programme in American Samoa (1979 to 1987). Office of Marine and Wildlife Resources, American Samoa Government. 49 p.

- Kearney, R. and J. Hallier. Interim report of the activities of the Skipjack Survey and Assessment Programme in the waters of American Samoa (31 May to 5 June; 15 to 21 June 1978). Skipjack Survey and Assessment Programme, Preliminary Country Report No. 9, South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 10 p.

- Mead, P. 1978. Report of the South Pacific Commission Deep Sea Fisheries Development Project in American Samoa (28 March to 2 July 1978). South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 13 p.

- Moana, A. and L. Chapman. 1998. Report of second visit to American Samoa. Capture Section, Unpublished Report No. 13, South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 31 p.

- Russo, G. Unpublished. American Samoa trial pelagic longline programme, project assessment, feasibility of establishing a chilled tuna fishery. Consultants report prepared for the South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia.

- SPC. 2003. Population statistics provided by the Demography Section of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, Noumea, New Caledonia.

- Whitelaw, W. 2001. Country guide to gamefishing in the western and central Pacific. Oceanic Fisheries Programme, Secretariat of the Pacific Community, Noumea, New Caledonia. 112 p.

- WPRFMC. 2003. Regulatory Amendment 4 to the pelagic fishery management plan of the Western Pacific region. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii. 57 p plus attachments.

- WPRFMC. 2002. Amendment 11 to the fishery management plan for the pelagic fisheries of the Western Pacific region. Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, Honolulu, Hawaii. 171 p plus attachments.